Where We Began – The Biomedical Model

For more than a century, the biomedical model — derived from Louis Pasteur’s germ theory of disease — has been the dominant force in Western medicine. Postulating that all disease is a product of a biologic defect (Conti, 2018).

The biomedical model of treatment assumes that symptoms are the result of tissue pathology. It also assumes that there SHOULD BE an organic explanation for ALL symptoms. Building on this assumption, it would be reasonable for clinicians to expect a proportionate amount of pain relative to tissue pathology. A visualized injury must be more painful than one less so, correct?

Face of pain!

Face of pain? Lady Gaga acknowledged that she lives with Fibromyalgia pain everyday.

Why This Is Insufficient (at least for chronic pain)

Because the biological concept of pain is simplistic and undeveloped, clinicians frequently minimalize patients’ accounts of pain (if not observed), which could result in the marginalization of patients. Even the best-meaning clinician might find themselves under treating patients’ pain and discounting emotional and psychological factors.

Where We Are Now – The Biopsychosocial Model

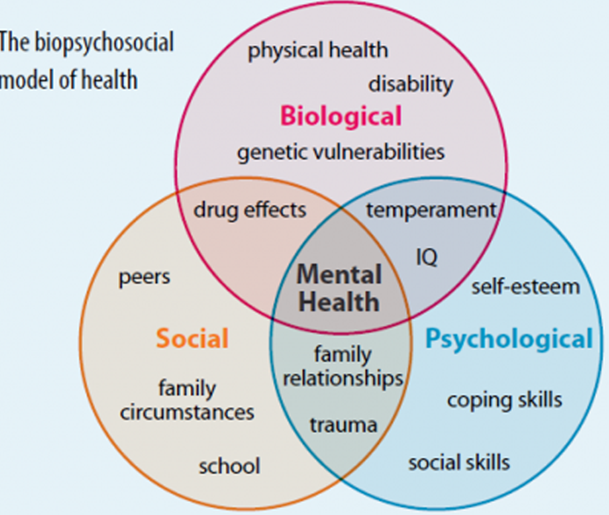

Melzack & Wall’s gate-control theory of pain (Melzack & Wall, 1965), and influence from the hospice movement, shifted the pain management paradigm, increasing the emphasis on cultural and psychological influences. It was this awareness, in part which propelled the biopsychosocial model of pain management forward.

The biopsychosocial model considers the patients’ needs from a biological, social (cultural), psychological and spiritual understanding. The treatment plan is created using a multimodal approach relying upon a multidisciplinary framework.

The first pain clinic in the U.S. in the 1960s, was started by specialists from 13 difference disciplines aiming to collaborate in a nonhierarchical manner (Collier, 2018).

(Biopsychosocial Model – Physiopedia (physio-pedia.com))

Improvement, but incomplete

Even with significant patient and clinician advocacy efforts, as well as “calls to action” at the National level (IOM, 2011; NIH, 2016; US Dept. HHS, 2019), we still have not been able to achieve the full benefits of multidisciplinary care in pain management. In part, this might be due to:

- Lack of education and understanding of patient needs in pain management amongst various disciplines?

- Not enough training provided/ or interest in pain management:

- Primary care

- Psychology

- Physical Therapy

- Lack reimbursement to care for these complex patients, unique needs

- Continues to be limited coordination of care amongst disciplines.

Where Should We Be Headed

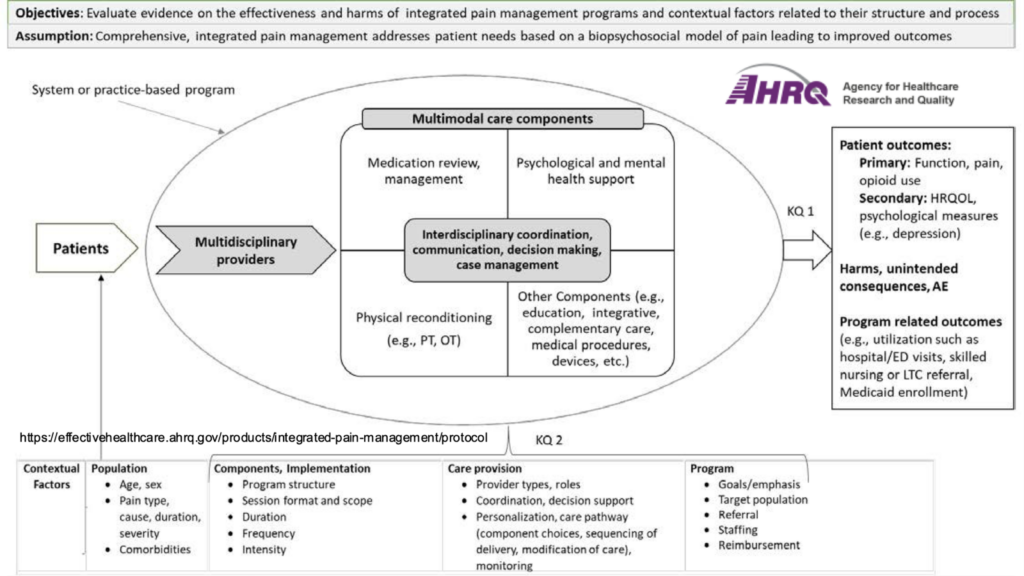

Integrated Pain Management Programs (IPMP), involve a multidisciplinary team focused on coordinated and integrated patient care that is individually focused and involves primary care (AHRQ, 2020). Components common to IPMPs included:

- Multidisciplinary case management

- Pharmacotherapy review algorithms

- Mental health services

- Proactive symptoms monitoring

- Patient self-management resources

Integrated Pain Management Programs | Effective Health Care (EHC) Program (ahrq.gov)

Well demonstrated in integrated care systems such as the Veteran’s Administration (VA), but can it be supported and funded in a private for-profit healthcare system?

The question is still on going as data is collected, looking at the cost and benefits (improved patient outcomes, decrease in health care utilization), amongst the healthcare systems who have currently embraced this model.

A parallel model is “the transitional pain service”. (Mikhaeil, et al., 2020). Again, possibly better implemented in an integrated health care system such as the VA.

The concept of the Transitional Pain Service (TPS) was created to effectively manage patients’ perioperative pain long-term if needed, maintain function, reduce opioid consumption, and monitor the efficacy of these interventions. Although TPSs were seen pre-2016, the 2016 CDC opioid prescribing recommendations fueled the fire in organizations looking to minimize indiscriminate prescribing of opioids post-operatively without a plan for efficacy, monitoring and weaning appropriately.

In Summary:

When it comes to superior outcomes in both acute and chronic pain management it takes a village. It also needs to be supported at an insurance and reimbursement level, and education must be provided to all healthcare providers early on in their training as well as through on going quality continuing education programs.

Register for a Skin Bones CME Conference Today!

Hit the reset button while earning continuing medical education credits at our CME conferences, where you can travel to a vacation destination; earn CME credits with like-minded nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and physicians; and ‘unplug’ while enjoying a new locale! Check out our upcoming Skin, Bones, Hearts & Private Parts 2023 CME Conferences and 2024 CME Conferences! At every event, the best of the medical community gathers to earn CME credits, network, and gain knowledge on dermatology, orthopedics, cardiology and emergency medicine, women’s health, pain management and pharmacology, diabetes, ER, and mental health. On-line CME courses and Virtual CME are also available so you have the option of earning CME credits online.

References:

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Effective Health Care Program, Rockville, MD. Research Protocol: Integrated Pain Management Programs. Content last reviewed December 2020. https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/products/integrated-pain-management/protocol

- Bokhour BG, Haun JN, Hyde J, et al. Transforming the Veterans Affairs to a Whole Health System of Care: Time for Action and Research. Med Care. 2020 Apr;58(4):295-300.

- Collier R. A short history of pain management. CMAJ. 2018 Jan 8;190(1):E26-E27.

- Conti AA. Historical evolution of the concept of health in Western medicine. Acta Biomed. 2018 Oct 8;89(3):352-354

- Institute of Medicine. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; 2011.

- Lentz T, Goertz C, Sharma I, et al. Managing Multiple Irons in the Fire: Continuing to Address the Opioid Crisis and Improve Pain Management during a Public Health Emergency. NEJM Catalyst Innovations in Care Delivery. 2020 June 22, 2020.

- Melzack R, Wall PD. Pain mechanisms: A new theory. Science. 1965;150:971–9.

- Mikhaeil J, Ayoo K, Clarke H, Wąsowicz M, Huang A. Review of the Transitional Pain Service as a method of postoperative opioid weaning and a service aimed at minimizing the risk of chronic post-surgical pain. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 2020;52(2):148-153.

- National Institutes of Health (NIH). The Interagency Pain Research Coordinating Committee. National Pain Strategy. (2016). Available at: https://iprcc.nih.gov.laneproxy.stanford.edu/National_Pain_Strategy/oversight_panel.htm.

- Peterson K, Anderson J, Bourne D, et al. Effectiveness of Models Used to Deliver Multimodal Care for Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain: a Rapid Evidence Review. J Gen Intern Med. 2018 May;33(Suppl 1):71-81.

- Research Protocol: Integrated Pain Management Programs. Content last reviewed December 2020. Effective Health Care Program, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/products/integrated-pain-management/protocol

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2019, May). Pain Management Best Practices Inter-Agency Task Force Report: Updates, Gaps, Inconsistencies, and Recommendations. Retrieved from U. S. Department of Health and Human Services website: https://www.hhs.gov/ash/advisory-committees/pain/reports/index.htm